Digital maps show yield potential

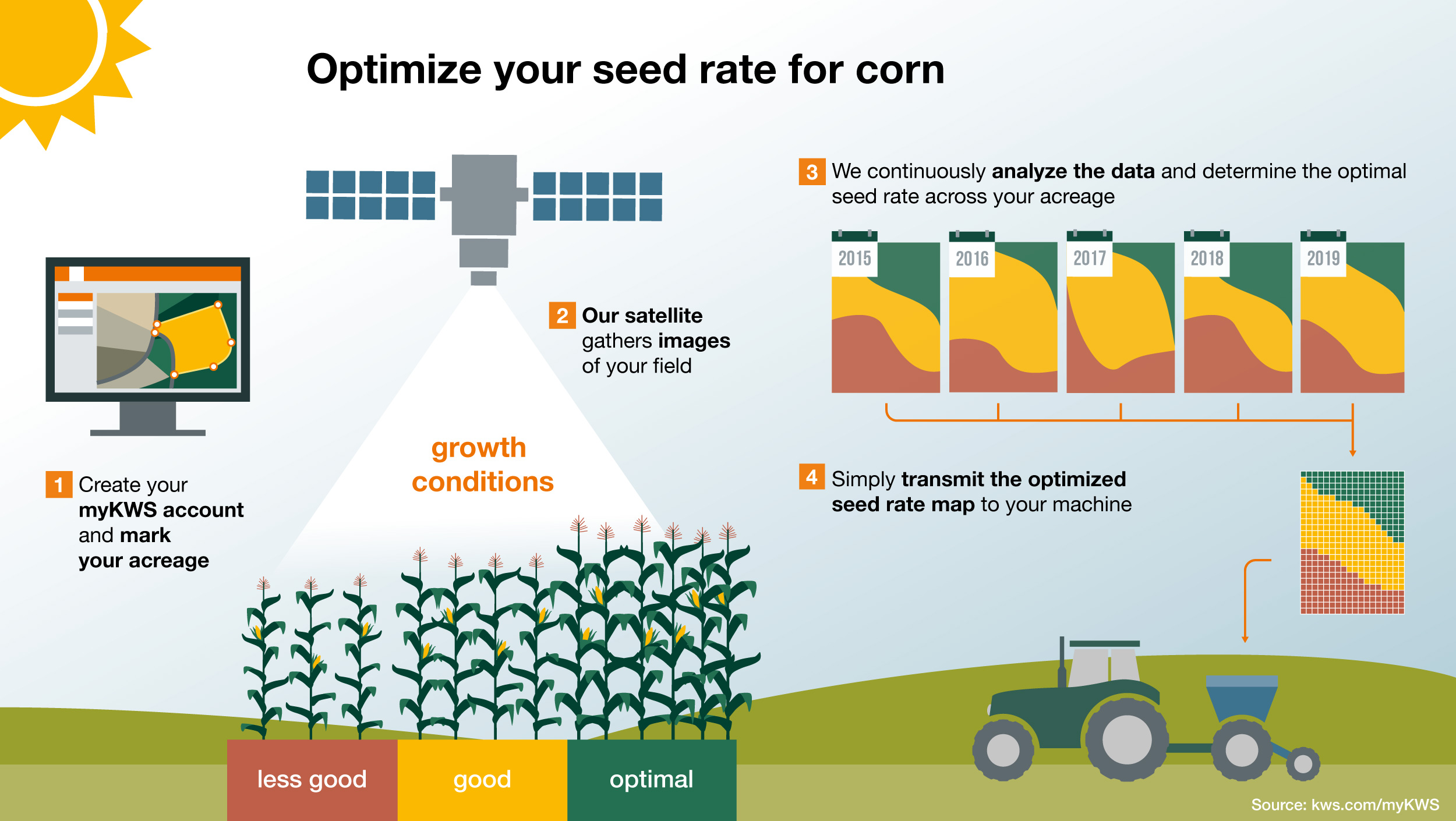

On the other hand, KWS’ systems use the concentrated force of big data and objective images from space. The Sentinel-2 satellite system of the European Space Agency (ESA) constantly supplies photos of the Earth’s surface. The satellites orbit our planet, and every five days or so they fly over the 3,200-hectare farm in central Italy where Simone Sebastiano works. The high-definition images enable the land cover to be identified: water, rock, forests, roads, fields and plants.

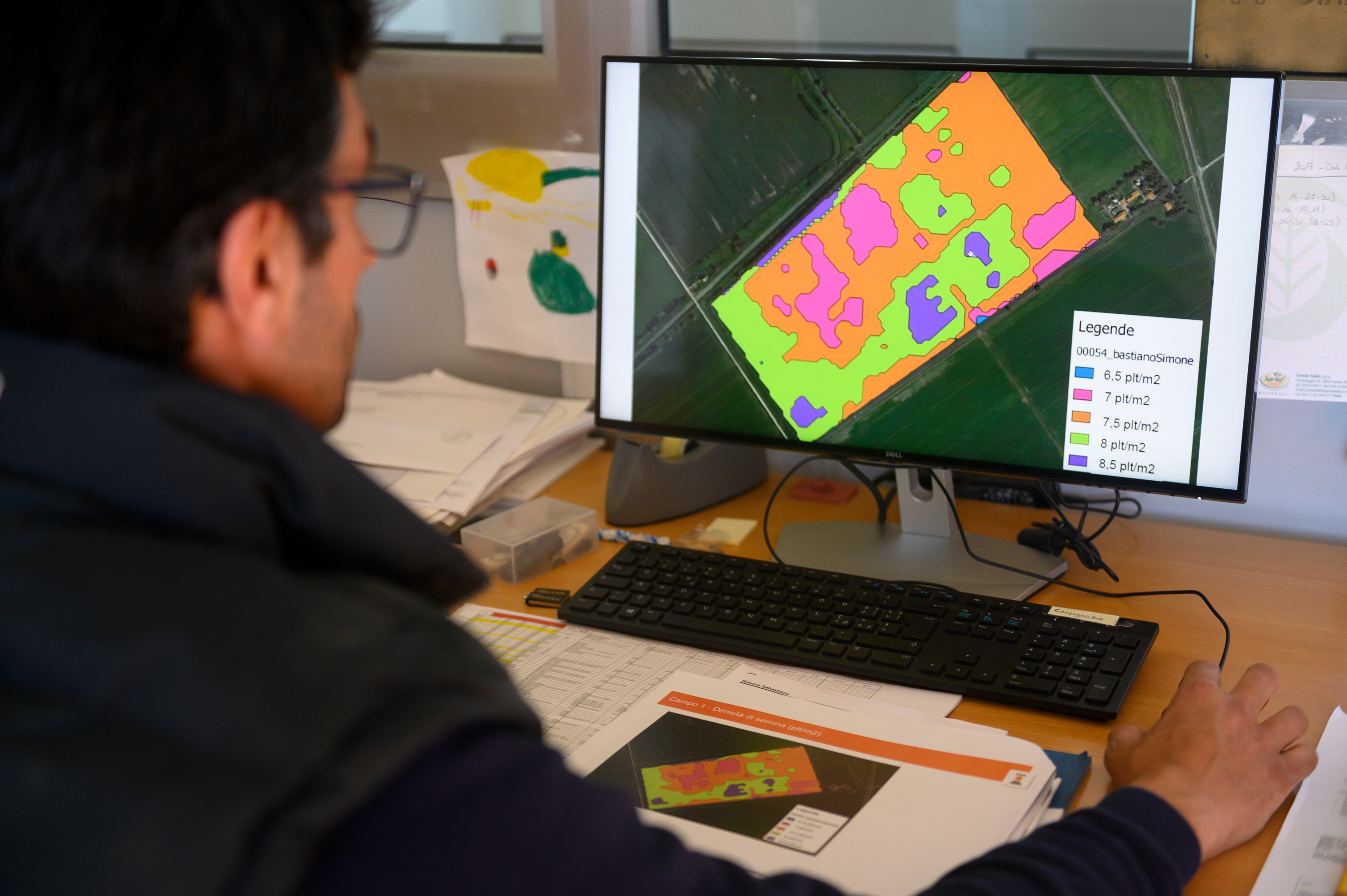

KWS has collected these images over several years and compared and analyzed them. The system uses this information to determine where more or fewer plants grow – down to a scale of ten by ten meters. A digital map created from the satellite data also shows Maccarese’s fields.

Bright colored areas extend across the virtual fields on the screen in Sebastiano’s office. The software displays the results from past years: The greener the hue, the more plants there were on the section in question, while red areas indicate a lower yield. KWS’ algorithm translates these findings immediately and then derives a recommendation on how much seed should be sown where. Shortly before it’s time to finish work, Sebastiano is satisfied with the planning and sends the information to his seeder with a click of the mouse.