Getting second wheat crops to perform

Milling wheat varieties are popular in the second wheat slot - helping to maximise grain quality, and produce higher yields with better disease resistance than other cereals in the second cereal position.

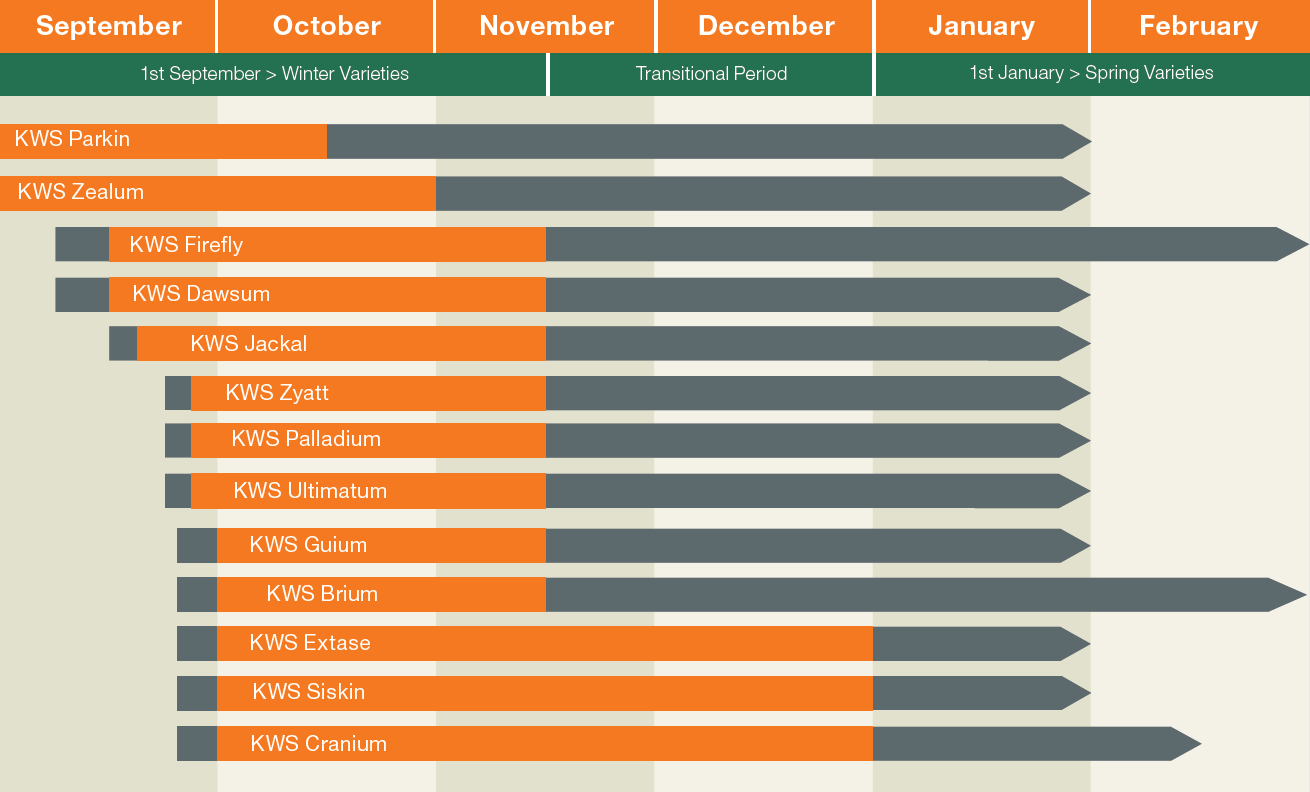

Here are the important factors of how to choose a second wheat, and the varieties that we recommend.

.jpg)